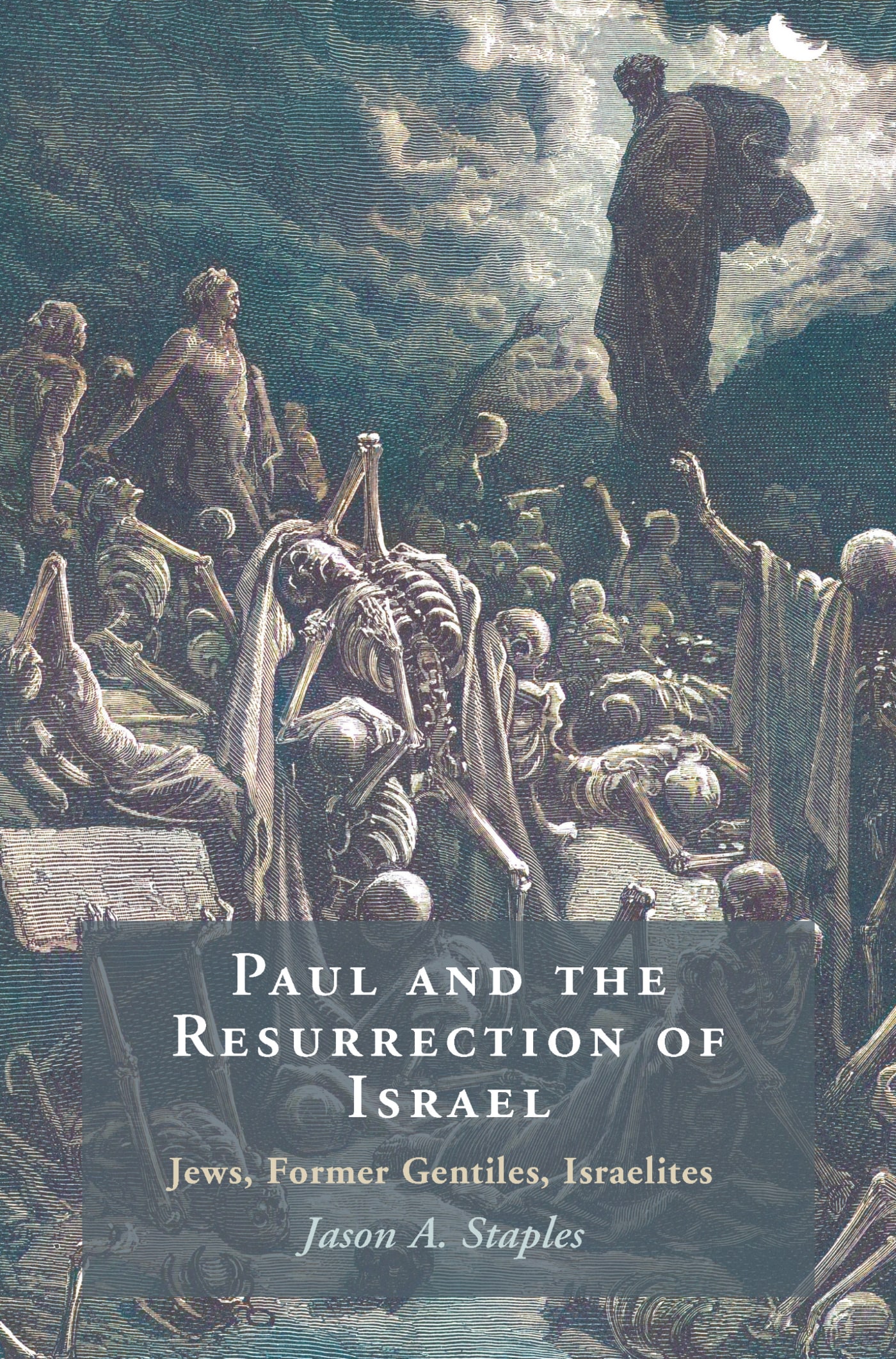

Beginning with the first publication of James Tabor’s B&I piece on Talpiot Tomb B, the Tabor/Jacobovici theory that this is the tomb of the earliest Christian disciples has hinged in large part upon their identification of the “sign of Jonah,” a nose-down fish spitting out a stick-man Jonah, on the front of one of the ossuaries in the tomb. The vast majority of scholars who have weighed in on the subject have strongly disagreed with this interpretation of the image as a fish spitting out a stick man, with most seeing the image as a relatively roughly done vessel of some sort, functioning as a nefesh on the front of the ossuary. The Tabor/Jacobovici camp have also further thrown their own theory into doubt by changing which lines supposedly function as the stick man’s arms and legs after James Charlesworth’s far-fetched claim that the name “Jonah” is actually scribbled into that area (addressed here and here), with some of the lines of the name also functioning as part of the stick man.

But before we can even discuss whether this stick man is in fact struggling for his life and therefore changing the position of his limbs, we first need to answer the question my wife (an artist herself) asked the first time she saw the supposed Jonah/fish: “Wait, did they even draw stick men back then?” It’s such an obvious question, but it has somehow (perhaps for that very reason) been overlooked so far. As it turns out, this is a pretty important question, since any interpretation of this image as the “sign of Jonah” depends on ancient viewers being acquainted with the phenomenon of representing human beings with a few quick lines—enough that the engraver of this ossuary would have carved such an unclear figure but still assumed the implied audience would interpret this set of lines as an upside-down kicking, struggling, limb-shifting human being.

We modern Westerners are quite familiar with stick-figures, so much so that we might assume they have always been the quick way to draw human beings. But as it turns out, after searching for analogous stick figures in antiquity—especially in this period of the ancient Mediterranean—I’ve come up completely empty. So have the other historians and scholars I’ve asked to take a look through the data.

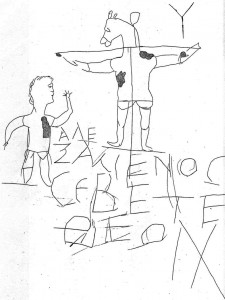

Human beings are depicted in all sorts of ways, but I have not found a single example of a modern-style stick figure in this period. Not one. The closest analogs look something like the Alexamenos Graffito, which features a donkey-headed man on a cross and another figure, said to be Alexamenos, worshiping his God (presumably the figure on the cross, a derogatory reference to Christian worship). But the figures in this graffito, which was found near the Palatine Hill in Rome, although crudely drawn, have distinct trunks and multi-line limbs (as you can see in the picture to the right).

As far as those of us who have looked into this can tell, there are no examples of stick figures from the Hellenistic period at least until Augustulus. Take a look at the vase art from that period: nothing even close to a stick figure. Below I’ve pasted some examples of human depictions in graffiti from second and third century Ostia, more of which can be accessed here:

It’s pretty clear that nothing here looks remotely like a stick figure. The human form is consistently represented with full limbs and trunk, even in graffiti. Even the ancient petroglyphs I’ve looked at have wide trunks denoting the larger width of the body than the arms and legs and show more detail than a modern stick man. The absence of stick figures in the ancient Mediterranean is really the final nail in the coffin for this “Jonah” theory, as it is highly improbable that the engraver of this ossuary decided to draw a human being in a way that would be familiar only to those living centuries after him.

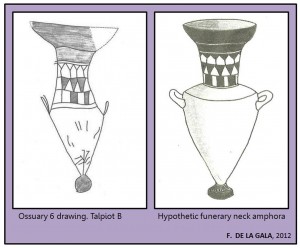

It is even more improbable that he would put this stick figure inside a non-stick-figure fish and then spend significantly more time and effort detailing the seaweed wrapped around Jonah’s head than he had spent on the entire figure of Jonah. Think about that for a second. It’s absurd, even ridiculous, to suggest that the engraver would spend much more time—and many more scratches—carving the seaweed than on Jonah himself or on the alleged inscription intermingled with Jonah’s flailing limbs. On the contrary, as Juan V. Fernández de la Gala has already shown (after pointing out nine incongruities that have yet to be satisfactorily rebutted), the “seaweed” is simply the artist’s attempt to represent shading on the vessel:

This theory has already been shown to be deeply flawed, but the fact that it is built on an anachronism, on the assumption ancient people drew stick figures, discredits it from the very start. This theory is the product of modern people seeing what they want to see—and what ancient people clearly would not have seen. Unless Tabor and Jacobovici want to claim that this also happens to be an unprecedented find of the first recorded stick man from that region and period in addition to being an unprecedented example of “the sign of Jonah” in an unprecedented early Christian tomb, this case is closed.

12 Comments. Leave new

excellent point! why put a stick man in a non-stick fish? (maybe a fish in a non-stick pan… 😉

This is a really helpful contribution, Jason. Thanks. I have never found the stick man theory plausible, for reasons stated on my blog, but this further detracts from the theory’s appeal. It’s curious that the “seaweed” is depicted in the same way as the “tail” of the fish, and some of the decorative patterns (“scales”).

I wanted to join in the fun. I love the way you guys give each other high fives on each other’s blogs and any opinion – even contradictory – that disagrees with us gets the secret handshake. First of all, since when are all you guys experts in ancient art? How many art historians have weighed in? Second of all, it is not implausible that more time would be spent on the seaweed than on the figure. One top Israeli scholar in art history who refuses to be named because he/she does not want to be attacked the way you are now attacking Prof. Charlesworth, wrote to me; “what is most interesting for me is the stick figure with the seaweed. It reflects a theological/psychological struggle in the artist. On the one hand, he wants to depict a human figure, on the other he does not. So he uses the ‘stick figure’ and he exploits the line in the Book of Jonah about the seaweed to avoid making eyes, nose and mouth.” Finally, the statement that there are no stick figures from that age and that we are reading back this modern invention into a time that did not know of it is plain wrong. You should really learn to use the search engine Google Images. Below is one particularly interesting image from a tombstone in Carthage, where you have a stick figure (Tanit), a rosette and fish (with a waistline), all themes that are present in our tomb:

http://i1165.photobucket.com/albums/q589/SimchaJacobovici/400px-Stele_with_fish_and_Tanit_sign-MBA_Lyon_1969-95-IMG_0552.jpg

Unless, of course, these are not fish but “hypothetical amphoras.” Maybe the stick figure of Tanit is not a stick figure at all, but a nephesh. Further, I provide you with a stick figure from Har Karkom in the Negev that pre-dates our tomb by several thousand years:

http://i1165.photobucket.com/albums/q589/SimchaJacobovici/HarKarkomPetroglyphs.jpg

If you don’t like that one, there are a few hundred more like it. Choose the one you like best:

http://israelrockart.com/english/ibex.html

BTW, on the last page of this month’s BAR, you have a Roman era coin from the southern coast of England that dates roughly to our period. It was minted in the UK around 30 BCE i.e., a little earlier than our tomb and, guess what, there’s a stick figure there alongside geometric patterns. But maybe Cargill will think it’s a Mr. Potato Head:

http://i1165.photobucket.com/albums/q589/SimchaJacobovici/coin.jpg

Maybe one day I’ll get a high five from you guys.

Simcha

Thanks for the reply, Simcha. A few quick observations:

1) The Tanit figure isn’t a stick figure (triangles aren’t sticks, and the Tanit iconography had a long tradition by this point), nor does it in any way resemble the sort of image suggested for “Jonah.”

2) I’m pretty sure those petroglyphs are nearly as far removed from the first century as we are. As you said, the one you posted pre-dates “your” tomb by several thousand years.

3) The coin is interesting, but it isn’t from the Mediterranean in our period. As your teammate Dr. Tabor has consistently pointed out, if you want to find a legitimate analog here, it should match the time and location, not something from the century prior and a different culture from what we’re looking at (it’s certainly not Roman or Jewish). It also doesn’t depict a true stick figure, especially since the “trunk” is raised pretty substantially, which is the way one depicts depth in a coin. Nor is it clear that the coin is depicting a human being—how many legs are we looking at there.

4) Another anonymous “top expert” who is afraid to back your case publicly, eh? Interesting.

5) If you guys find a good analog from the period, I’d be happy to withdraw my critique here, but it’s important that we ask questions like this to ensure avoidance of anachronism.

6) Even if a stick figure turns up, I don’t think you’re going to find an example of a stick figure inside a non-stick figure.

If you’re really that desperate for a high five, I’d be happy to give you one, should we ever meet in person. Heck, as a former athlete, I could even throw a good butt slap in there if you want.

You make a good point. Why sully it with the canard about the nefesh tower, which no one really believed.

I didn’t say anything about a nefesh tower. Not every nefesh is a tower nefesh. Even as a vessel, this may function as a nefesh image on the ossuary, that’s all I was saying.

Here’s a comment from page 56 of Dina Teitelbaum, The Relationship between Ossuary Burial and the Belief in Resurrection (2007):

“Among the various motifs the amphora is a favorite one (fig. 16). It is assumed that amphorae surmounted some of Jerusalem’s tomb monuments (note 200: RCat. 34.) and an amphora set on a trumpet foot pictured on a nephesh may be an indication of such a trend. (note 201: RCat. #325). Generally, it appears singly….”

Also, Teitelbaum concluded that ossuary use was not correlated with resurrection or afterlife belief.

Hi Jason,

As a former athlete you should know the rule about not moving the goal posts. What I was responding to is your misleading statements that; “Wait, did they even draw stick men back then”? Notice the “back then”. The implication being that stick men are modern inventions. You answered that question by stating that this is an important question because you weren’t sure that “ancient viewers” were acquainted with stick men. Again, no mention of Israel or the 1st century. For good measure, you then state that “after searching for analog stick figures in antiquity” – I repeat, “antiquity” – you came up with nothing. You did say that you were especially interested “in this period of the ancient Mediterranean” but you also state that you came up “completely empty”. When you did bring up images to argue against us they weren’t from Israel and they weren’t from the Second Temple Period. Rather, you call the stick figure “modern style” i.e., some kind of modern invention, and you state that “the closest analogs” are things like the “Alexamenos Graffito” from Rome. You use that figure to contradict us. You then bring up figures from Ostia to further contradict our stick figure. You finish off stating that “even the ancient petroglyphs” that you’ve looked at seem to have “wide trunks denoting the larger width of the body than the arms and legs and show more detail than a modern stick man”. Again, you call the stick man “modern” and you find no parallels anywhere, any time, including ancient petroglyphs. You finish with a flurry; “The absence of stick figures in the ancient Mediterranean is really the final nail in the coffin for this ‘Jonah’ theory”.

Then, when I show you a Phoenician Tanit that looks remarkably like our stick man complete with “bubble head”, you come up with some lame answer that “triangles aren’t sticks”. They actually are! Then you say that the petroglyphs that come from the right area i.e., the Negev are “far removed from the 1st century”. Wait a minute, didn’t you say that even the “ancient petroglyphs” were not stick figures? Then when I show you a Roman coin – which is essentially the same culture that ruled Israel at the time – with a stick figure, you argue that it’s not a “true stick figure”, whatever that means. Suddenly, you seem to be talking about a “stick figure inside a non-stick figure” and you want it to be from the 1st century and from Israel i.e., “it should match the time and location”.

The point is very simple Jason. You said that you came up empty and I showed you that you can’t use Google properly.

High five,

Simcha out

Simcha,

I believe that goalposts have been moved, but Jason wasn’t the one doing the moving. 🙂

The plain and obvious context of his argument (which you have most casually subverted) is “What stick figures are there in 1st century around Talpiot?” (That’s — excusing the pun — the crux of the observation, is it not?)

Jason couldn’t find any from that period and place and instead posted some examples of what he thought came as close as he could from other places and times. All of your examples were more of the same, as they also did not meet these criteria. 🙂

The Tanit, is only *superficially* similar. Tanits symbolize a bust with outstretched or raised arms, not a stick person with arms and legs. They are quite often solidly filled in (another thing that I’m sure Google will reveal in an image search), and the one you linked to is merely stylized as an outline. Conflating a Tanit with a “stick figure” is a simple category error.

The petroglyphs fail the criteria of time (*far* too old; 1000s of years).

The coin is Celtic-Roman (a quarter-stater from Kent, England!) and fails the criteria of distance (*far* too far away).

Peace,

-Steve

PS – On the subject of anonymous “experts,” I’m aware of individuals (arguably “top scholars”) who are hesitant to join in and don’t want to be named, not because of any fear from the blogging community, but because they don’t want to seem to endorse or inadvertently give publicity to your claims (like what happened in the aftermath of the Princeton symposium on the first Talpiot tomb; more context subversion 🙂 ).

PPS – I’ll see your high five and raise you a drink. 🙂

come on professor jacobovici … to play word games like this really insults the readership of this blog and any other blog or forum discussing this issue. jason clearly marked out that he was talking about this period, as you yourself note, and separated it off with em dashes. to jump to petroglyphs from millennia before after you’ve admitted that is little more than cognitive dissonance.

as for stick figures … by definition they have single lines for body and arms and a simple circle type thing for a head. there is no attempt to add any ‘dimension’ and a rriangle does not a stick figure make.

as for the coin, if you read carefully in the current issue of BAR, where you no doubt saw it, it comes from hitherto unknown pre roman layers at folkestone villa, so to build on the previous comment, it fails both in ters of distance and time.

Even the rock art uses fairly thick lines, much unlike “Jonah.”