Back in the spring of 2008, I took Bart Ehrman’s seminar on “Literary Forgery in the Early Christian Tradition.” At the time, Bart was working toward his book, Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Christian Polemics, which he later popularized into Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Aren’t Who We Think They Are, and the rest of us benefited from his having collected extensive resources on the subject and suffered together through Wolfgang Speyer’s Die literarische Fälschung.

But that’s not the subject for today’s post. The second week of the class was on the Disputed Pauline epistles (or, as Bart prefers, the Deutero-Pauline epistles)—that is, 2 Thessalonians, Colossians, and Ephesians, each of which is thought not to have been written by the historical apostle Paul by a reasonably high percentage of critical scholars. One of the articles we read for the class was from Bart’s Doktorvater (and now my Doktorgroßvater), Bruce Metzger, “Literary Forgeries and Canonical Pseudepigrapha,” JBL 91 (1972): 3–24.

We read this article after going through earlier (19th century) materials on the same subject and were all surprised to find numerous examples of verbatim or near-verbatim agreement between Metzger’s article and Alfred Gudeman’s 1894 chapter on “Literary Frauds among the Greeks.” I’ll list the examples below, with underlining where there is substantive agreement.

On pp. 66–67 of his chapter, Gudeman says the following:

Finally, I draw attention to one other instance of a literary forgery which is of particular interest, because it furnishes the only example, at least the only one that has come under my observation, of a literary fraud perpetrated from a motive of pure malice, it having been designed to blast the reputation of one of the greatest historians of Greece.

Apropos of a statue in Olympia, erected to Anaximenes of Lampsacus, the traveller Pausanias takes occasion to add a few details concerning this man and to give some of the reasons for his being thus honoured. We learn, accordingly, among other things, that Anaximenes was the author of a number of historical works, and that he was the inventor of extemporaneous speeches, whatever that may mean. The statue in question had been erected to him by his grateful fellow-citizens, because he had on one occasion saved the town of Lampsacus from destruction at the hands of the enraged Alexander, by a very clever ruse which he practised upon the great Macedonian. After relating the story, Pausanias continues as follows: This same Anaximenes once played an ingenious but very scurvy trick upon his enemy, the historian Theopompus. Being himself a sophist, and skilled in imitating the style of the sophists, he wrote a book, in which he slandered Athens, Sparta, and Thebes; and then counterfeiting to perfection the diction of the historian, he sent the work to these cities under the latter’s name, in consequence of which all Hellas was intensely exasperated at Theopompus.

Metzger’s article includes the following (pp. 6–7):

Occasionally a literary fraud was perpetrated from the motive of pure malice. A counterpart in antiquity to the modern fabrication in czarist Russia of the scurrilous “Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion” was the attempt of Anaximenes of Lampsacus to blast the reputation of one of his contemporaries, the historian Theopompus of Chios (4th cent. B.c.). According to the account of Pausanias, Anaximenes, being himself a sophist and skilled in imitating the style of sophists, once played a scurvy trick by composing, under the name of his rival Theopompus, bitter invectives against the three chief cities of Greece, Athens, Thebes, and Sparta. He then sent a copy of the slanderous work to each of these cities, with the result that the unfortunate historian was henceforth unable to appear in any part of the peninsula.

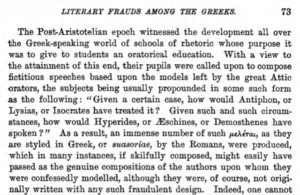

These are relatively minor, and if this was the extent of the verbatim agreements, we’d probably not have thought much of it. But there’s more later in the piece. On p. 73, Gudeman says:

The Post-Aristotelian epoch witnessed the development all over the Greek-speaking world of schools of rhetoric whose purpose it was to give to students an oratorical education. With a view to the attainment of this end, their pupils were called upon to compose fictitious speeches based upon the models left by the great Attic orators, the subjects being usually propounded in some such form as the following: “ Given a certain case, how would Antiphon, or Lysias, or Isocrates have treated it? Given such and such circumstances, how would Hyperides, or Aeschines, or Demosthenes have spoken?” As a result, an immense number of such μελέται, as they are styled in Greek, or suasoriae, by the Romans, were produced, which in many instances, if skilfully composed, might easily have passed as the genuine compositions of the authors upon whom they were confessedly modelled, although they were, of course, not originally written with any such fraudulent design.

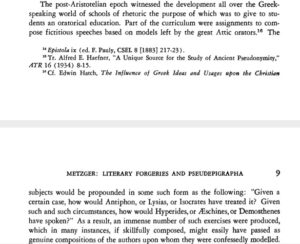

Metzger’s version (pp. 8–9) is as follows:

The post-Aristotelian epoch witnessed the development all over the Greek- speaking world of schools of rhetoric the purpose of which was to give to students an oratorical education. Part of the curriculum were assignments to compose fictitious speeches based on models left by the great Attic orators. The subjects would be propounded in some such form as the following: “Given a certain case, how would Antiphon, or Lysias, or Isocrates have treated it? Given such and such circumstances, how would Hyperides, or Aeschines, or Demosthenes have spoken?” As a result, an immense number of such exercises were produced, which in many instances, if skillfully composed, might easily have passed as genuine compositions of the authors upon whom they were confessedly modelled.

Yikes. This passage is lifted nearly verbatim from Gudeman, and with no attribution. I must confess to chuckling at the irony of this happening in an article on literary forgery and pseudepigrapha—and in a paragraph on mimesis, no less. But there’s more, as Gudeman says (p. 64):

For there is scarcely an illustrious personality in Greek literature or history from Themistocles down to Alexander, who was not credited with a more or less extensive correspondence.

Metzger’s version (p. 10) is as follows:

There is scarcely an illustrious personality in Greek literature or history from Themistocles down to Alexander, who was not credited with a more or less extensive correspondence.

Yet another example of verbatim agreement, and it’s made even worse by the fact that Metzger nowhere cites Gudeman’s chapter in his article. There may be more examples, but these were the ones I have in my notes from back in 2008, and I haven’t been interested enough to work through the articles more closely since then. Needless to say, this led to some interesting discussion in the seminar that week.

For his part, Bart didn’t think it likely that these were intentional plagiarisms. Instead, he thinks they were likely the result of Metzger’s peculiar method of taking notes for research projects, which involved writing down quotes and notes on the 3×5″ notecards that he carried with him everywhere and then would file for his projects. Bart’s thought was that Metzger probably wrote these quotes down on the cards but wasn’t always careful about recording the source on every card, making it too easy for Metzger to lose the connection between the quote and the source, accidentally misattributing what he had on a given card as his own words or notes (which he regularly composed on those cards as thoughts came to him) rather than a verbatim quote from someone else.

From my own reading of prior generations of scholarship, such sloppy documentation seems to be the norm rather than an exception, and in fairness, when the technology involves post-it notes or 3×5″ cards rather than Bookends or Endnote, it’s definitely more difficult to keep track of everything.

Nevertheless, some of us, including myself, were (and remain) a bit more skeptical of that explanation given the degree of verbatim agreement here and the fact that some of the material is reworked in exactly the way one would expect if someone knew he was plagiarizing. That said, either way, it’s a reminder of how important it is to have a rigorous and reliable research process that makes one less likely to plagiarize.

I must confess to being a bit terrified of accidental plagiarism in my own work, a fear that has only been increased by a few occasions in the last couple years in which either I or another reader/reviewer have noticed a quote where somehow the footnote containing the citation for a marked quotation had fallen out in the process of editing. Fortunately, all of these have been caught to date, but it’s definitely an occupational hazard of which I’m especially wary.

(Disclosure: I receive affiliate income from the purchase of any books through the links above.)